As a Minnesotan, February is a signal that the warmth of spring is so close yet so far away (seriously, last Thursday the high was two degrees!). And as someone deeply committed to fighting for racial justice and equity, this month is a powerful opportunity to reflect on the disparities that exist in our public education system due to race, power, and privilege, and recommit ourselves to eliminating these inequities.

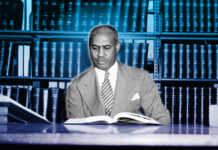

The evolution of Black History Month dates back nearly 100 years. In February of 1926, Carter G. Woodson, a Black public school teacher began “Negro History Week” when he realized that little to no Black history was being taught in schools. Mr. Woodson saw “Negro History Week” as a direct challenge to a power structure that made clear that Black history was unworthy of learning, and he wanted to facilitate a means through which teachers could illuminate the way racial power operated in America.

In a short amount of time, 80% of predominantly Black schools adopted the week. By 1976, “Negro History Week” expanded into the national Black History Month that we know today.

But the truth is, Black history is American history. Black history is world history. We must not limit our celebration of Black excellence to a single month. Nor should we limit our efforts to eliminating racial injustice and inequity. This work cannot take a day off, which is something we strongly believe at Educators for Excellence (E4E).

As E4E’s Director of Policy and Partnerships, much of my work has centered around our advocacy campaign to address the total lack of diversity in our public education system.

Our campaign, “Reimagine, Represent: Strengthening Diversity through Education,” is predicated on the fact that an appalling 40% of public schools across our country do not have a single teacher of color on staff. Forty percent! And even more shocking and disappointing is that Black teachers only make up approximately 7% of the teaching workforce.

When you consider this data, it is difficult not to think about the Black teachers in the late 1920s and 1930s who made the decision to teach Black history to their students, thereby challenging the power structure that deemed Black people and their rich history not worthy of study or praise. Not only were those teachers educating students who looked like them and had a shared history, but they were also bringing a perspective that traditional textbooks left out.

This is an experience that so many students of color across the country still do not benefit from today. Not only do they not see themselves reflected at the front of the classroom, but in a recent national survey, 41% of public school teachers say that their schools are not reliably providing a welcoming and inclusive environment for students of color.

The lack of progress in diversifying our teacher workforce is particularly frustrating in light of research that Black teachers are more likely to have higher expectations of their Black students, more likely to provide culturally relevant teaching, develop trusting relationships with their students and confront issues of racism through teaching.

Black history is history, period, yet it has become common practice to pack hundreds of years of deep and rich history into 28 days of lessons, celebrations and acknowledgment. This is simply unacceptable. Not only do we do ourselves a disservice by constricting it into one short month, but simply celebrating the bravery of Harriet Tubman or Rosa Parks does not get to the heart of why “Negro History Week” and subsequently Black History Month were created.

I challenge you not to just use this month to celebrate the contributions of Black Americans to our society, but instead to honor the richness of Black history throughout the year. More importantly, I implore you to reflect on the power structures that exist as a result of our racist past and join our efforts to eliminate racial injustice and inequity by increasing the diversity of our teaching workforce. Students are counting on us.