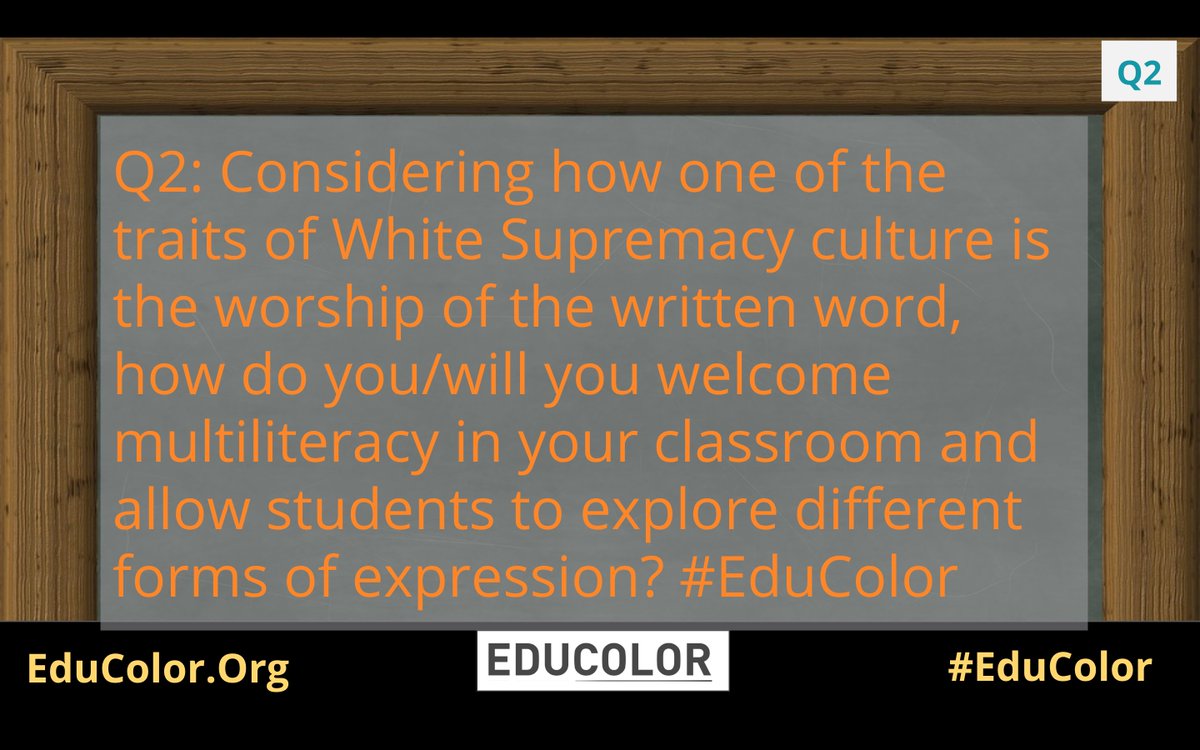

There’s a major force in the education world that has attempted to claim ownership over the term “equity.” From tweets questioning the value of literacy and preparation programs (like mine) that ask teachers how they create spaces for “alternative forms” of demonstrating knowledge, since “worship of the written word is a tenet of White supremacy,” to think-pieces that paint the research-informed community as too White, a dangerous precedent is being set. This kind of thinking furthers an “us” versus “them” mentality and leaves no room for dissenting opinions or disagreement.

This ideology, while well-meaning, can be easily misinterpreted. It can mislead new and idealistic teachers into embracing a methodology that does nothing on its own to elevate academic outcomes.

Still, questions like these shape and mold the minds of self-described anti-racist educators. We rally and claim that until we solve poverty, our children cannot be expected to learn or perform well on standardized exams. Yet, when equity advocates are confronted with stressed-out teachers, the professional development they offer amounts to “have good relationships,” “find the positive” and “White people—y’all just need to do better.”

In place of a meaningful discussion, what has emerged from all this is a one-dimensional view of equity. In addition to stifling opposing views, this perspective has become more about changing the minds of teachers rather than changing the outcomes for students.

NO ONE OWNS THE ‘EQUITY’ CONVERSATION

The educational left claims it not only owns the equity conversation, but that such conversation is changing educational practice. However, educators like me are concerned that, so far, the equity conversation isn’t centered enough on actual classroom practices to make meaningful change to student learning and success.

From #EduColor to #DisruptTexts to the Pacific Educational Group, the intent and mission of these organizations seem to be focused on changing the individual minds of teachers in lieu of specific, actionable strategies to improve the abysmal state of literacy for students. In that branch of equity work, the major assumption is that if you just make teachers more aware of their individual biases and roles in systematic and systemic racism, teachers will teach better and students will learn better. This has yet to be demonstrated.

So perhaps the issue at hand isn’t whether or not there is an equity backlash, but in determining the best way to address it. On one extreme, we have teacher-leaders organizing chats or participating in literature circles digesting “white fragility” in a philosophical discussion of how to change classroom practices to make them more inclusive. On another, we have policymakers mandating top-down accountability measures, thus attempting to force teachers into compliance. In its own way, the same “y’all just need to do better” is happening on both extremes of the aisle. Sadly, neither extreme is doing much to actually improve what matters most for our students: classroom instruction.

RESEARCH IS CRITICAL TO IMPROVE TEACHING AND LEARNING

Thanks to the growing research movement, a burgeoning middle is appearing, replete with its own conferences, publications and Twitter chats to address classroom instruction. Groups like researchED and the Reading League offer educators opportunities to learn about research-based classroom practices and connect with like-minded colleagues. These opportunities show how equity conversation can be more closely coupled with concrete steps to improve instruction and student learning.

For example, at the recent researchED Philadelphia event, Dr. Sonja Santelises, CEO of Baltimore Public Schools, discussed the impact of real estate redlining on schools and drew parallels to the “educational redlining” that takes place when certain kinds of curricula are reserved for Whiter, wealthier students. At the same time, she presented the work she is leading to ensure Baltimore teachers have the training and curriculum they need to to ensure all children read well, think mathematically and can succeed in school and in life.

“Equity work” must go beyond merely discussing race philosophically, in the hope that those discussions lead to increased outcomes. Doing “the work” has to come with the understanding and recognition that while tools exist to help students learn better, most of us teachers don’t know about them, because big-name publishers and teacher preparation programs are driven by philosophy and ideology, not evidence and research.

Let’s stop separating students from basic tenets of literacy, from a knowledge of history and literally from one another into individualized interest-based books or locking them into Chromebooks, such as with the commonly-used Reader’s Workshop model. At a minimum, we should be building community around a shared text. Ironically, the current iteration of “progressive education” seems to be centered around continually individualizing learning, rather than collectively empowering students.

What passes now for progressive education has largely been co-opted by publishers whose curricula do not rely on the science of how we learn to read. They also lack a basic understanding that, once a child has learned the mechanics of reading, it takes background knowledge—understanding of the subject and knowledge of the key ideas and vocabulary involved—to develop reading comprehension.

They’ve sold us a lie and our students are the casualties.

Given that reality, while the current and loud discussion around equity in the classroom is important, it is missing a critical piece of the puzzle: an evidence base with which to address instructional inequity.

A FOCUS ON OUTCOMES IS A FOCUS ON EQUITY

Perhaps some of us don’t talk about equity in the same way, but this does not mean that we can be dismissed as reinforcing White supremacy, being a part of a “backlash” against equity or setting a trap using the master’s tools. In fact, researchED is one of the few places to discuss tangible, practical solutions to the poor educational outcomes to which Black, Brown and poor students are being subjected.

So let us stop insisting that wanting children to have strong academic outcomes is anything other than socially just, or is somehow not equity-focused. This is an opportunity to make equity actually mean something for our practice as teachers, and not let equity become a buzzword meaninglessly attached to everything because no one really knows what we mean when we say “the work.”

Solutions to the problem of inequity in the classroom exist. Research about how kids learn and what has worked elsewhere can help tell us what those solutions are—far better than any courageous conversation ever will.

This post originally ran on Education Post here.